Several weeks ago, I spoke to a large group of elementary students in grades 4 to 6. One teacher had asked her class to prepare questions in advance, which were written on pieces of paper and handed to me at the front of the room. I did my best to get through them but ran out of time. I stuffed the rest of the questions into my bag.

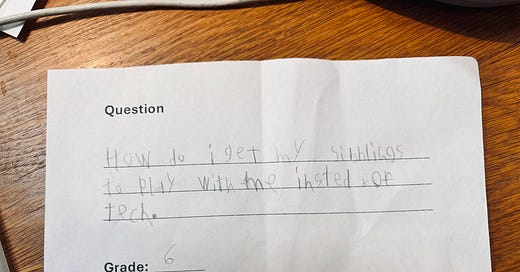

Back home, I found myself flipping through them—there’s something irresistibly cute about children’s handwriting—and one question jumped out at me. A child had written, “How do I get my siblings to play with me instead of tech?” I paused, looking at the crookedly formed words, and my heart lurched a little. The question was practical, straightforward, and yet I sensed an underlying confusion, a sense of loss and disorientation, that filled me with sadness. It read like a small, mournful cry for help.

What have we done to our children, if they can’t even play with each other anymore, and would prefer the companionship of a device over that of a real live human? What happens to our families when one child’s source of “entertainment” fuels another’s sense of loneliness? There’s something wrong about that picture.

I recognize that not all siblings are close friends or playmates, but they certainly don’t stand a chance at becoming any closer if a device is in the way. It’s an impediment that will only accentuate the distance.

‘It’s Not Your Fault!’

What would I say to that child? I’d say, “I’m really sorry to hear that your siblings are playing with tech more than with you. It’s not your fault. The devices are designed to be highly addictive, and it can be hard for some kids to stop using them and start playing real-life games if a parent isn’t making strict rules. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t stop inviting them to play.”

I would encourage the child to tell their family about the presentation I’d done, to teach their siblings some of the interesting facts they’d learned that day, to suggest concrete ideas for games to play with their siblings that might tempt them away from their devices, e.g., “Here’s a Frisbee. Could we toss it around for 15 minutes?” or “I have this new Lego kit. Would you help me get it started?” or “I’m trying to build a fort in the backyard and need you to help me nail down a sheet of plywood” or “Here’s the hamster; let’s build her a cardboard maze.”

I would respond with a tone just like his initial question, practical and straightforward, so as not to make him feel self-conscious. But if I could speak to the parents, I would be tempted to let out a little more emotion.

‘Get Rid of It!’

I would want to say, “Have you thought about your kids feel? Do you actually think that, deep down, they prefer immersing themselves in shallow Internet culture over experiencing the embodied, juicy realness of play in a physical world? What kind of memories do you want them to have? And do you know that the cost of distraction is loneliness? Are you aware that one of your children is hurting, on some level?”

Then I’d urge them to get the tech out of the house. I’d tell them that they are allowed to change their mind, to walk back decisions already made. I might add, “Have you ever heard that the day you give a child a tablet or a smartphone is the last day they’ll ever be more interested in anything else?” The device is simply too powerful. It hijacks the human brain with tantalizing rewards and constant novelty. It provides instant entertainment at the slightest twinge of boredom.

These devices are known as experience blockers, which impede kids’ engagement with the real world in the ways that they need in order to develop optimally. We humans are hardwired evolutionarily to do this. We need it desperately; and yet, these devices stunt potential. They may keep kids quiet and subdued in the short-term, but the kids miss out on so much in the process.

They don’t get to practice getting along and solving problems. They don’t get to make up their own games, with complex plot lines and imaginary characters, and cast themselves and their siblings and friends in those roles. They don’t get to explore spaces beyond adult eyes, using their physical bodies in new, challenging ways. They don’t find themselves lying on the grass on a hot summer day, looking up at the clouds overhead and thinking about how tiny they feel in relation to everything else.

The Necessity of Boredom

I would tell the parent, “Do you know about boredom, and how good it is for a child?” In our society, we tend to assume that we need to entertain or keep a child entertained every minute of the day. But that’s not true. Children need to be bored periodically. Boredom is a crucial transition state that spurs kids on to new ideas, activities, discoveries, hobbies, and skills. Indeed, without it, it’s hard to imagine how we’ll produce the next generation of artists, writers, and scientists.

Precisely because boredom is uncomfortable, children of all ages are motivated to move beyond it and find things to—and they always do. Kids are marvellously adept at entertaining themselves, when forced to do so. But if they have access to a tablet or a smartphone, that is where they will turn, instead of toward their own ingenuity and curiosity.

Like a cuckoo bird laying its eggs in another bird’s nest, the device will always squash other nascent ideas; or at least it will captivate the child’s attention just long enough to make them think, “It’s not worth the effort to build the fort, start reading the book, get out the paints, bike to my friend’s house.”

If I got really worked up, I might be tempted to ask a parent, “Why did you have more than one kid?” A huge upside of multiple children is the fact that they can play with each other. I tell my children all the time that, no, I do not want to play with them—that’s not my job, nor am I interested in engaging with active play (that’s just my personality, and every parent is different)—but I’ve given them each two siblings, which are built-in playmates. That’s a pretty sweet deal, when you think about it.

What Can You Do?

If the parents were open to advice, I would say, “There are two main things you need to do to get siblings off tech and playing with each other.” First, the devices need to go away. Keep them out of sight, out of reach; ideally, get rid of them. No child needs a tablet or a smartphone before the age of 16, at minimum. Even that’s debatable. A laptop can do many of the same things, while being less addictive than a touchscreen.

Second, fill the void that’s left when digital play is swapped out for analog, offline play. This requires going through a replacement phase, which might feel rocky for a while, but over time it will stabilize. You can sign your kids up for some organized activities, if you wish, to help fill the time. But you can also add toys, games, books, sporting gear, craft supplies, and other open-ended “loose-part” toys to your household, so that there are actual real things for your kid to do whenever they want to play.

And then you step back. You let them go.

You say yes when they ask to bike around the block (assuming they have basic traffic navigation skills) or ask to bake a cake after school. You let them turn up the music and dance wildly. You don’t complain when they pull all the cushions off the couch to make a blanket fort in the middle of the living room, though you can remind them it has to be put back before bedtime. You let them leave their Monopoly game on the dining table. As soon as they ask, you move the car so they can play basketball in the driveway. You set up the hose so they can make mud in the sandpit—and then help them clean up afterward. You let them climb the very tall tree and resist the urge to tell them to come back down. You agree to let them try riding a neighbour’s pit bike, because you know they can do it, even though you keep picturing a crash (it never happens).

You do all of these things because this is what childhood needs to be. You accept the mess and noise and chaos, recognizing that it’s part and parcel of the amazing privilege of having energetic children and adolescents in a home—and that it is so much better than having silent, sedentary children tucked behind closed bedroom doors, exploring and pushing the boundaries of a virtual world rather than a real one.

And then you watch relationships grow and flourish between siblings because there’s no longer a device getting in the way. Yes, they will fight, viciously at times, but they will have occasional moments of beautiful connection, and hopefully those will increase in frequency as time goes on. Learning how to coexist with people who drive us crazy, whom we may never have chosen to be our friends if we’d had the choice, is superb training for adulthood.

Set the Standard

Finally, I might ask that parent, “What are you doing?” Are you modelling a preference for human companionship over digital substitutes? Do you sit with friends, invite them over to your home, share cups of tea or glasses of wine, talk about your challenges and excitements? Or do you lie on the couch, scrolling on Instagram or watching Netflix?

Not that we must seek out others’ company all the time—there’s nothing wrong with lazy, quiet evenings—but ideally, our children should be able to observe regular social interactions among adults that are not mediated by technology. If we want our children to play and interact with real humans, not phones, then we must do the same. As parents, we are never not modelling, and kids pick up on everything. Resisting “technoference” will also make us better parents.

I will never meet the child who asked me that thoughtful question, and I can only hope he took something away from my talk that he was able to share with his family that night. I hope his parents can detect the loneliness that came through his handwritten words and recognize the fact that so many of these devices, when allowed to colonize our children’s childhood, perpetuate a profound sense of isolation—and leave us feeling alone, even though we may appear to be together.

Our kids deserve better.

You Might Also Like:

In the News:

If you’re looking for advice on how to get kids moving more, there is a great new resource just released by the California Partners Project. The ‘Movement and Outdoor Activity Family Guide’ helps parents to determine what might be getting in the way of their kids’ physical activity and how to tackle those barriers. There are lots of practical ideas for what families and individuals can do, both indoors and outdoors, as well as encouragement to promote more childhood independence and overcome parental fears.

I consulted for the first guide that was released several months ago, on social-emotional health. There are more guides coming in the series, all of which are designed to help parents navigate the tricky new waters of raising kids in a tech-saturated world.

New Opinion Piece – Globe and Mail

I write a monthly column for the Globe and Mail, Canada’s largest newspaper. My most recent one ran on May 5, 2025, titled “Is your kid 18? Here are 11 life skills they should have mastered by now.”

Not surprisingly, it generated a flurry of opinionated comments. They are amusing to read—such a mishmash of love and hate, and I’m fully aware I can never please everyone—but a good reminder of the ongoing importance and relevance of this conversation around childhood independence. We are raising adults, after all, not children, and training for adulthood starts takes a very long time. We’d best get to work.

Radio Interview: Does Quebec’s full school phone ban go too far?

That’s the question I was asked in an interview this past weekend for CFRA Live, and you can imagine the answer—no!!! The province of Quebec is doing precisely what Ontario should have done a year ago, when it announced its feeble “ban” that still lets students carry phones on their person. You can only imagine how well that goes. I wrote a scathing piece about it for the Globe several weeks ago: “Ontario’s toothless phone ban isn’t working. It’s time to rethink it.”

You can listen to the 9-minute radio interview clip here.

It's easier for children not to be addicted to tech if they are denied access to it at all in their early years. In my family, the youngest members were denied it until they were of an age where they could understand how to use it wisely; that's really the only solution. Individuals can play ball with this, but institutions are slow to embrace any sort of change...

That child’s question made my stomach drop reading it. That child has assessed their value to their sibling and found they rank lower on the list than they’d like due to the dominance of tech. So sad as a generation develops a sense that their value, their own self-worth plus their value to others around them, extends only as far as they engage online or virtually. Thank you for sharing this story.