I told someone the story about my 10-year-old son riding his bike alone to Walmart, two kilometres from our house. He wanted to buy a Beyblade toy with his own money. I didn’t have time to take him, so he begged to go on his own. He had to cross four lanes of traffic (at a stoplight), navigate a busy parking lot, lock up his bike, find the toy, do the transaction. It seemed to take forever, but finally he came home, far more delighted by his independent outing than by the toy itself.

The person I was talking to said, “I could never do that. I wouldn’t be comfortable letting my kid bike to any big box store. That’s impossible. I don’t even want to let him go to a different aisle in the grocery store.”

That got me thinking about how childhood independence doesn’t happen overnight. It is a long, slow, cumulative process that parents need to engage in deliberately to build capability from the very beginning. (That doesn’t mean you can’t start anytime.) In our culture, there are commonly acknowledged stages of training to teach kids how to sleep and eat and talk and read and move their bodies, but we don’t have that as much when it comes to teaching kids to be independent in the world.

And yet, I’d argue that it should be incorporated into a child’s upbringing. It should be viewed as a necessity. We should introduce small opportunities for independence that get progressively more challenging as the child gets older, to the point where an older teen is completely prepared to leave home after high school and knows how to do all the things that a young adult needs to do to be successful on their own.

But how and where do you start? I have some general suggestions, based on my own experience raising three sons who are now 10, 13, and 15.

Take them with you.

It can be tempting to leave kids behind when you run out to do errands, but how else are they going to observe and learn how adults operate in the world? Sure, it takes a lot longer when you have kids in tow, but they’re absorbing everything they see, especially if they’re not on a device.

Walk or bike places.

That is the mode of transportation that they will be using eventually, so it’s smart to get them accustomed to doing it, as well as familiarize them with the safest local routes. Both you and your child will feel less daunted if they are geographically oriented in the world. I used to test my kids’ ability to cross the street, asking them to be the leader and tell me when it was clear. They loved that game when they were little, and it made me feel better, knowing they were attentive.

Talk to strangers.

Interact with the people you meet. Your child is watching and learning. It makes the world seem a lot less scary by generating familiar faces and showing that most strangers are nice, well-intentioned people. It will make your kid more confident asking for help if he or she ever needs it. Furthermore, a child who isn’t cowed by strangers is less likely to be treated as a victim, and is thus safer out in the real world.

Ask your kid to do things.

Start small, like sending them down the same aisle in the grocery store when they’re a preschooler to select a familiar brand of cereal. Then expand to the rest of the store, a neighbouring store, or a store down the street. Run errands at the same time and agree to meet back at the car. Send them to drop off books at the library, to pick up mail at the post office, to retrieve a parcel from a delivery location.

This expands as they get older. Now, I sometimes tell my oldest that he’s in charge of making dinner and needs to go to the grocery store (with a backpack and my credit card) to buy the ingredients for whatever he wants to make.

Explain the process.

Tell them how much something will cost, how much money they should take, what change they should expect, how they should plan to transport something back to the house. My boys like having these details; it makes them feel better prepared for a new task.

Start with groups.

There is strength in numbers, and that’s where siblings are particularly handy. Older kids will feel more confident if they’re backed by siblings, and younger ones see what the older ones are doing and want to emulate it. By the time my 10-year-old biked to Walmart alone, he’d already done it several times with his teenage brothers, so it was not a totally foreign concept. He knew the drill.

Walk to school.

There are many reasons why walking to school is great for kids, from moving their bodies first thing and getting fresh air to allowing them to process their thoughts and explore the world a bit, but it also establishes their rightful place in the world. It gives them a sense that, even though they’re small, they belong independently in their town or city. They have a daily task, a destination, a purpose that does not need to be validated by the presence of an adult. I believe that does wonders for a child’s confidence.

Say yes to independence.

If a child asks to do something on their own, and you know deep down that they’re capable of it, then you should probably say yes. My oldest wanted to go trick-or-treating on his own at age 10, which seemed reasonable, so I agreed as long as he took a friend. I worry that when parents let their own fears get in the way of kids doing things they want to do, it can cause the child to second-guess their ability and become less confident in the long run. It makes them think, “Oh, maybe I can’t do that, because Mom doesn’t believe I can.”

Push them a bit.

Seek out opportunities that are at the edge of their comfort zone. I once asked my middle son, who was 8, if he wanted to stay home alone for 10 minutes while I dropped off his brothers at an appointment. He said no, preferring to tag along to the appointment, which was fine with me; but the point was, I’d challenged him to do something that he hadn’t considered before and may have boosted his confidence. The next time I asked, maybe he’d feel ready. Sure enough, it didn’t take long before he wanted to try staying home alone.

Give them chores.

Assign work and then step back and let them do it. It will not be up to your standards, but that’s OK. Patiently explain what they can do to improve, show them, and try again. Doing chores is not merely about getting work done; it’s about training discipline, giving kids a sense of usefulness, and expecting them to contribute to the household that they are part of.

Celebrate milestones.

Make a big deal out of the fact that your child did something on their own. Acknowledge it at the dinner table in front of the rest of the family. Tell their grandparents. Let your child see that you’re proud of their forays out into the real world and the things they’re doing on their own. They need to know that you’re not trying to hold them close, that your desire for them is to do more and more on their own.

This isn’t easy, of course. But it’s a necessary part of parenting that is too often overlooked. Independence does not come naturally to all children; it must be taught. And that is your job as a parent, after all, to raise an adult.

I’d love to hear from readers about what some of your tactics are for helping kids become more independent, so please feel free to share in the comments below.

You Might Also Like:

The Profound Pleasure of Physical Tasks

When Adults Help Kids

On Taking Responsibility

New Podcast Episode:

Several weeks ago, I had a great conversation with pediatrician Dr. Tim Jordan for his podcast, Raising Daughters. Obviously I am raising sons, not daughters, but my advice is applicable to all children! You can see and listen to the episode here on YouTube.

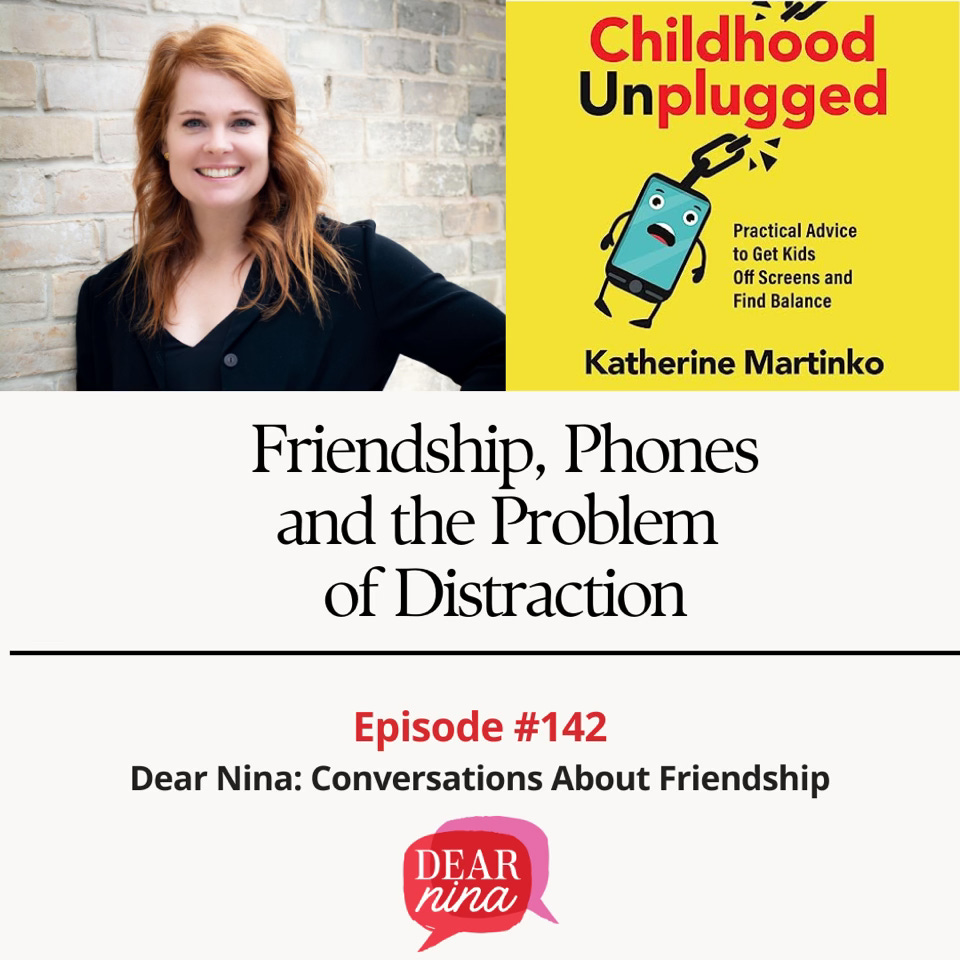

And if you missed it, there was another wonderful discussion with Nina Badzin on her podcast, Dear Nina: Conversations About Friendship, that just went live last week. Please have a listen here on YouTube or on Spotify or on Apple Podcasts.

Guest Lecture at McMaster University – April 24, 2025

If you happen to be in the Hamilton, Ontario, area on Thursday, April 24, I will be giving a guest lecture at McMaster University, 7-8 PM. The event is free, though pre-registration is recommended. I’m very excited for this!

Next week, I’ll be in Grand Rapids, Michigan, speaking on April 29, so stay tuned for that!

A Small Request:

I am able to write this newsletter twice a week and keep it open to the general public, thanks to generous readers who enjoy my words enough to sign up for a paid subscription! It’s entirely a labour of love and it takes a LOT of time and effort to do. Paid subscribers are a sign that I’m on the right track.

This is maybe the most important theme you write on. I’ve noticed since the publication of The Anxious Generation that Haidt and his collaborators have basically stopped writing about the phones themselves, and have shifted almost entirely to their “step 0” (the loss of community) which leads to “step 1” (loss of independent play) which leads to step 2 (phone-based childhoods).

You were on this theme earlier and in a more helpful way for us godless urban liberals 😝 (Haidt’s milieu seems to be writing as if the only way to restore community and childhood independence is to move to a religious-based intentional community).

I get a little thrill every time you write down! in public! under your real name! that you leave an 8 year old at home alone for a short time, or let a 10 year old go to a store alone. We do that too, but we’re very cautious about who we tell.

We have a friend who works in the Ministry of Children, Community, and Social Services here in Ontario and I’m trying to get her fired up about this stuff. She has horror stories about Child Protective Services being called on parents who let their kids ride public transit without parents (and yes, there’s a racial element to it). We are never going to get to widespread acceptance of this kind of childhood independence while the nuclear-apocalypse-level threat of a CPS report hangs over parents.

We (my wife and I) have raised four daughters; all are adult now.

I could not agree more with all your recommendations: walking to school, to groceries, doing chores, trying to cook—with mixed results :) . Once, the two older sisters took a bus to get to a store or so—I don't remember—and on the way back they took a bus in the wrong direction. They realized that they were going wrong way; they asked, got out, found a bus stop in the opposite direction, got back home.

Your boys are extremely, extremely lucky to have such a wise parent.