Many parents give their kid a smartphone because they think it will make them safer. There is a sense that having this most advanced form of technology in their pocket will somehow protect them from a “dangerous” real world. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. I’d like to unpack some of the reasons why this justification rubs me the wrong way—and what I think parents should strive to do instead.

It Puts a Huge Burden on a Single Device

As amazing as smartphones are, they can break, run out of battery, get lost, stolen, or fall into puddles. And if you haven’t taught your kid how to navigate the world without relying on a device, they’re going to be in big trouble if anything happens to their phone. Parents should ensure that their child has real-life coping skills for handling crises, like knowing how navigate a city, talk to strangers, borrow a phone to make an emergency call, ride public transit on their own, walk real distances, and more.

Phones Distract Kids

I had a memorable conversation with a mother of two teenage girls in Vancouver who do not have cell phones. She told me that her daughters describe being hyper-aware of who’s around them at all times. They know if there’s a creepy person standing too close for comfort, and they move away. They’re alert and attuned to their surroundings. That’s not the case for their friends, however, who huddle over their devices in public spaces, headphones on, staring at the screen, oblivious to who’s around them. They are oddly vulnerable, and yet (wrongly) perceive themselves as safe just because they have a phone in their hands.

Smartphones Are a Portal into an Ugly World

It’s ironic that phones are handed over as a so-called safety mechanism when, in reality, they are a portal into the worst of the world. As Jonathan Haidt writes, children are overprotected in the real world and underprotected in the virtual one. We set them loose in a space that’s rife with overly mature content, where we parents are absent and unable to offer the contextualization that is sometimes desperately needed.

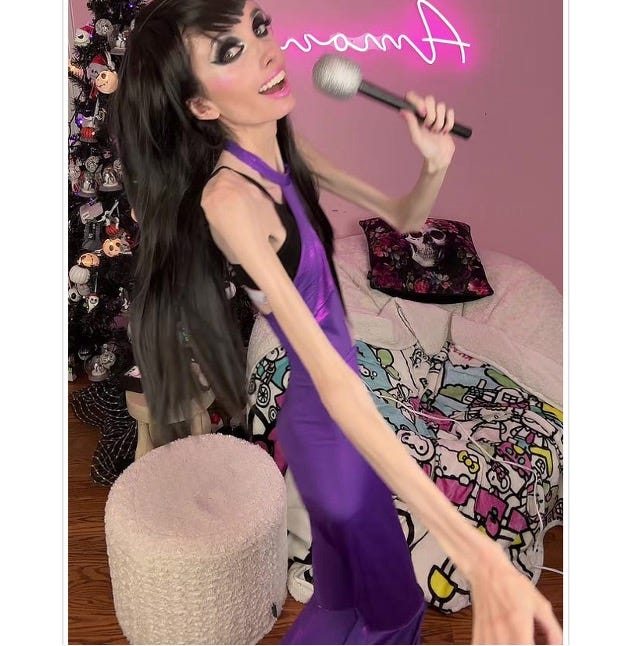

Our kids see everything from inane fluff to extreme violence, porn, and radical politics. They are exposed to assaults on their body image and mental health through self-diagnosis by TikTok influencers who promote eating-disorder videos and things like the “corpse bride” diet, popping antidepressants like candy and calling them “hot girl pills”. To quote essayist Freya India, social media puts young people “on a conveyor belt to someplace bad.” Very little good can come of it.

Then there’s sextortion, which is a serious and growing problem. Rates are up 150% in the past 6 months in Canada, according to CyberTip, and the number of online luring reports has surged 815% in the past five years.

Our parental attention is in the wrong places:

Kids Must Individuate

There is a natural process of separation that must occur between parent and child, particularly as child gets older. Teens need to do things independently from their parents, and smartphones undermine that because they make communication so easy and frictionless.

I remember the time I totalled my parents’ car in downtown Toronto when I was 17. Deeply upset, I called them from a pay phone—and they didn’t pick up. They were hiking in Algonquin Park that day, and no one had cell phones. So, I had to deal with the mess myself. The car was hauled away by a tow truck, I talked to police, and eventually got a rental car that I drove three hours home. It was a blur of confusion—I never really quite understood how the process worked—but the fact is, I handled it on my own.

There is a huge difference between dealing with a problem alone and calling Mom or Dad to sort it out for you over the phone. It is hard, but it builds maturity, experience, and confidence.

Studies have found that when kids are closely overseen by their parents, they become complacent and even resentful over time. Teens in the Netherlands and France were found to be less likely to respond to their parents’ calls and texts when they knew they were closely watched, and even less inclined to ask for help when they really needed it.

The Solution? Give Them Simpler Devices

I understand the desire/need to communicate with kids, especially if they’re older and going places on their own. But we don’t have to give them smartphones to ensure that.

Flip phones (and their various upgraded modern-day offshoots, like the LightPhone II, WisePhone, Mudita Pure, and Punkt MP02) are still a thing! They enable calling and texting, and some of the fancier ones support helpful tools like podcasts and alarm clocks and calculators, minus the Internet browser, social media apps, and camera.

Computers are effective ways to communicate, as well. My kids use iMessage on our family desktop computer to text their friends, which is great because it requires them to come inside, sit down in a common area, and log in to read messages, rather than carrying a device in their pocket that they are tempted to check every minute of the day. Communicating then becomes a conscious choice, not a compulsive action. It protects their independence and preserves their mental wellbeing.

Your Child Can Always Reach You

I frequently get texts from unknown numbers, which are messages from my kids sent from other people’s phones. They tell me they’re staying late after school or going to so-and-so’s house. I appreciate the little updates, which give me a rough idea of where they are, but I also trust them to navigate the world on their own. As long as they know where to find me, I feel OK with it.

We’d be wise to give more serious consideration to what constitutes “safety” for our children, and to realize that the online world is far darker place than we’d like to believe. As a school principal told me recently, “Most parents have no idea what their kids are seeing or doing online.”

Meanwhile, the real world has gotten almost unbelievably safe in recent years, with violent crime and death rates plunging across the board. There’s never been a safer time to be a kid out in the world, and yet parents keep choosing to hand over devices that pose an infinite number of new, and arguably worse, dangers.

Again, kids are overprotected in the real world, underprotected online. Let’s reverse that.

You Might Also Like:

I’ve Finally Figured Out When My Kids Can Get Smartphones

Don’t Ask for Parenting Advice on Social Media

What I’m Reading & Listening to:

I highly recommend this fabulous interview between Jonathan Haidt and Bari Weiss on Honestly: “Smartphones Rewired Childhood. Here’s How to Fix It.”

I read two brand new books while on vacation in Belize.

The first was Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout by Cal Newport, a good dive in how to apply yourself to meaningful long-term projects in a world obsessed with hustle culture. His main principles: “Do fewer things. Work at a natural pace. Obsess over quality.” It was thought-provoking, but if I’m being honest, a bit disappointing compared to his earlier Digital Minimalism book.

The second was Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren’t Growing Up by Abigail Shrier. I found this to be fascinating; I didn’t agree with everything she said, but it was a fast-paced and provocative book that pushes back against the idea that so many kids need therapy when, in fact, a good dose of resilience and independence might do them a lot of good.

In Other News:

My new website is now live! Please check it out to learn more about what I do—and yes, I am available for speaking events, both live and on Zoom. I love talking to groups of all sizes about the importance of digital minimalism and practical ways to implement it.

I recently set up pledges for The Analog Family. If you enjoy my work, please consider making a financial pledge. This newsletter is a labour of love thus far, but it takes a lot of time and energy! Pledges are a wonderful motivator for this work that I consider to be more important than ever.

You can also show support by buying my book and leaving an Amazon review!

That screenshot with the quote about the child watching porn with the parent in the next room--my heart hurts.

If only I had encountered your refreshingly practical perspective before we made decisions with our teens about their smartphones! I recognize my own paranoia around needing to be able to reach them as a MAJOR player in creating the problems we're dealing with now, and I dearly wish some of my choices in this department had been different.