Cal Newport is one of my favourite writers on the topic of technology. His 2019 book, Digital Minimalism, had a profound influence on me, opening my eyes to the necessity of putting digital media in its rightful place and not letting it take over every aspect of our lives. I appreciate how practical his approach is; he is a computer science professor, so he recognizes technology’s utility in our lives, while advocating for a cautious consideration of its trade-offs.

In a recent email newsletter, he offered advice that I think is critical to any discussion about how to establish a more balanced relationship with our devices:

“Fixing your relationship with digital tools requires that you fix your analog life first. It’s not enough to stop using problematic apps and devices, you must also aggressively pursue alternative activities to fill the voids this digital abstention will create: read books, join communities, develop hard hobbies, get in shape, hatch plans to transform your career for the better. Without deeper purpose, the shallow siren song of your phone will become impossible to ignore.”

We talk so much about the necessity of reducing screen time and getting off one’s phone, but we don’t talk enough about what is supposed to replace it. With adults spending an average of 2.5 hours per day on social media alone (not counting other forms of phone-based entertainment), that is a significant amount of time that suddenly needs to be reallocated toward something else.

It makes sense that many of the popular “phone-life balance” hacks don’t last. They are temporary solutions to a bigger problem, which is that we have forgotten how to do other things. Unless we can spark that interest again, we don’t stand a chance again the frictionless allure of a device that offers instant gratification as soon as we feel the slightest inkling of boredom.

Things vs. Devices

I sometimes wonder if our society’s precipitous decline in mental well-being is linked not only to the dramatic increase in screen time, but the corresponding loss of doing real things. Author Matthew B. Crawford argues that the experience of making things and fixing things is essential to our flourishing as humans, and that something vanishes “when such experiences recede from our common life.”

Crawford quotes philosopher Albert Borgmann, who says “things” are different from “devices.” Things are objects we master, such as a musical instrument. Devices are objects that do work for us, such as a stereo. Borgmann says, “A thing requires practice while a device invites consumption.”

In other words, we need more practice and less consumption in our lives. But reducing consumption does not automatically lead to practice; it must be actively sought, and that requires conscious choice, persistence, and stubborn adherence to routine.

Speaking of (literal) practice, every November I dust off my violin to start preparing for what is possibly the world’s most unusual production of Handel’s Messiah—a concert that takes place in the bowels of an old barn, surrounded by cows, horses, and sheep. For several weeks, I dedicate my evenings to practicing an hour of violin. Most of the time, this is not what I feel like doing, but the reward is getting to be part of such an exhilarating performance.

Related Article: On Reclaiming Leisure

What Did We Do in the Past?

We need to ask ourselves: What did we do before smartphones dominated our time and attention? When I think back on my rural TV- and Internet-less childhood, I remember hours of playing outside, going on long hikes with my parents, visiting the library, playing board games, and countless baking projects. My cousins and I would have at-home spa nights and dance parties in the kitchen. We ate a lot of popcorn.

When I left home at 16 to move overseas and eventually attend university (without a cellphone or TV for the first couple years), I spent free time writing, reading, listening to music, practicing instruments, and hanging out with friends. I studied foreign languages and spent a lot of time walking around strange cities. I bought groceries, cooked for myself, and invited new friends over to eat so I wouldn’t feel alone.

Now, I have a busy family with three kids in elementary, middle, and high school. There’s very little free time, but in a way, that makes resisting the smartphone even more challenging because it would be so easy just to dip in and out whenever there is a slight lull in the chaos. Instead, I stick to a rigid workout schedule, going to a local gym 4-5 times a week after work, making dinner, reading books in the evenings, and going to bed early. (I have a no-Netflix-during-the-week rule, but it ends up being no-Netflix-almost-all-the-time because I conveniently forget it exists on my laptop.)

Rekindle Curiosity

Newport says, “Aggressively pursue alternative activities to fill the void.” We as adults must find other things to do if we want to get off our phones. There has to be something waiting on the other side of the device, something that beckons to us, even if it takes upfront effort to get into.

Set those things up for yourself—whether they are old interests or new things you’ve always wanted to try—before you attempt to curb your phone use, because without that structure, it’s far too easy to slip back into your old habits, and you could feel very frustrated. Sign up for volunteer work, join a community group, or pay for a gym membership that holds you accountable. Make firm plans and put them on the calendar.

And then, give it time. Hobbies and skills are a long-term game, and you may not feel yourself improving for several months; but stick with it, and you’ll start to see the payoff from engaging in these high-quality leisure activities. Set goals for yourself and pursue them with determination. Your social life and your health can’t help but improve. You will feel calmer, more satisfied, more alive. Ultimately, isn’t that what we all want?

You Might Also Like:

A Small Reminder:

If you enjoy reading The Analog Family, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription! I write this newsletter because I love it, and I believe it serves a valuable purpose in our world today, but it’s not my full-time job, as much as I’d love it to be. Maybe someday it can, thanks to enough reader support! Thanks to everyone who already pays even when they don’t have to. It’s hugely appreciated.

The Anxious Generation: I’ve Joined the Team!

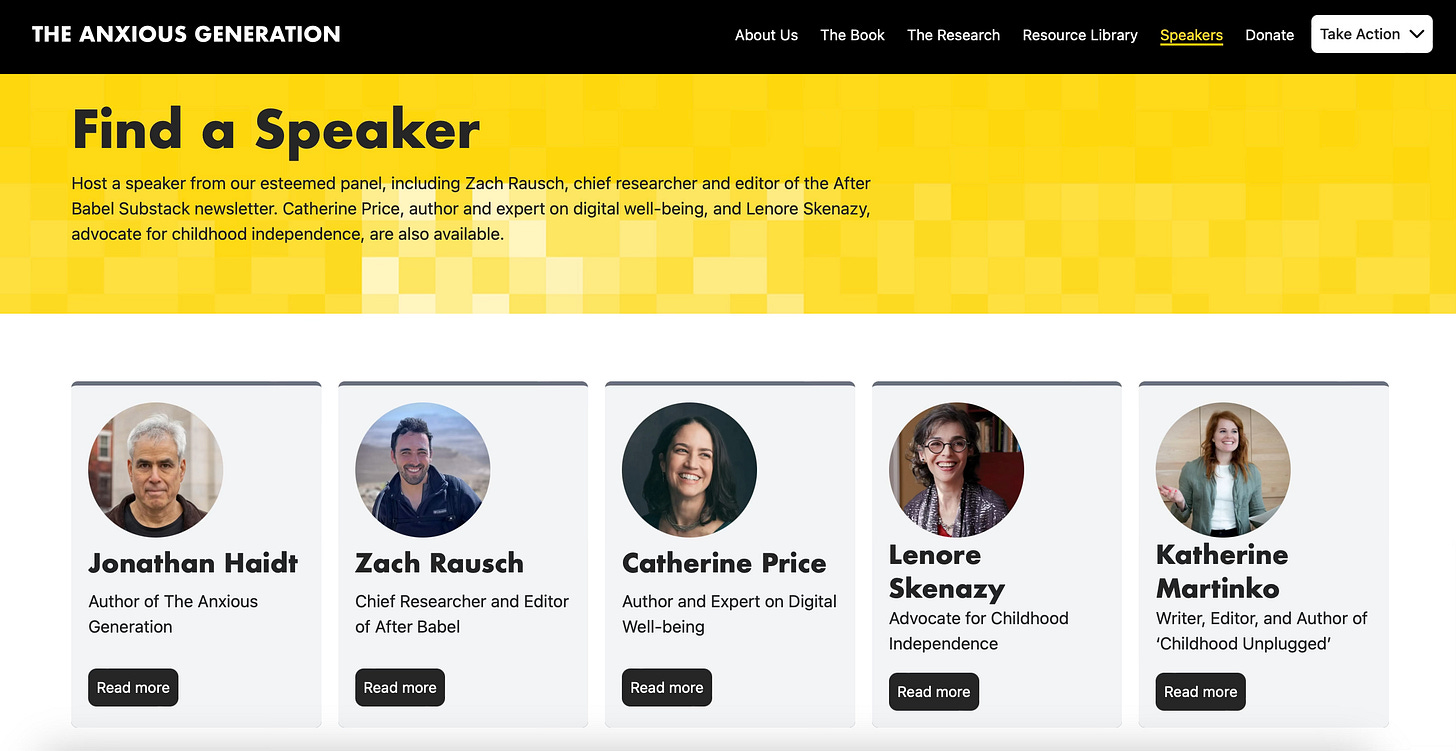

If you’re looking for a speaker on digital minimalism, I’m now on the roster with some other incredible writers and thinkers. Please reach out if you’re interested in booking a talk.

As a Gen-Zer who spent most of my high school and college years using technology as an escape from familial dysfunction and undiagnosed chronic health issues (as a means of dissociation, essentially), when I began living alone for the first time two things became immediately apparent to me:

1. I had no basic skills at all. I did not know how to budget, how to grocery shop, how to cook, how to clean, how insurance worked, how to care for my car, how to plan my time - etc. I had not yet had a full time job or serious financial responsibility.

2. I was a very narrow sliver of a human. All of my knowledge and experience was either from a liberal arts education which I barely made it through (but which benefitted me greatly!) and the internet.

When I began dating a wonderful, well-rounded man my senior year of college, I realized the interior and technical (in the sense of "techne" or "skill") poverty that I possessed. He had played sports, was very fit, knew how to cook, knew how to entertain, knew how to pour drinks, had been paying his way through college, had had at least five different jobs which taught him different people skills, money skills, etc. He had a wealth of experience to talk about, and his athleticism and knowledge of the world and people rendered him comfortable in just about any situation.

Meanwhile, I felt like I was just waking up, and to a world which I was woefully unprepared to live in. Everything was new, difficult, and alienating: putting together outfits, cooking meals, making meaningful conversation, dealing with my health issues - and even thinking about exercising, trying to entertain people, trying to navigate social dynamics -- nearly every basic human thing outside of reading, praying, and scrolling online felt herculean. Being with him, I felt ashamed - I saw myself as a shell of a human being, underdeveloped in almost every way. My time spent online had stunted me. We had spent the past eight years of our lives very, very differently, and it showed.

I've known for ages that screens are my way of coping with familial pressure and dysfunction (my family, ironically enough, attempted to be very strict with screens, but largely failed), and for nearly 10 years I have tried to reduce their presence in my life.

Only after achieving some degree of peace in my "analog life" (slowly learning how to do the basic human things such that I no longer need to escape from ordinary life) have I been able to make meaningful reductions in my screentime.

And now, I am exactly where you describe - ready to fill my life with good and beautiful things (books, audiobooks, walks, working out, musical instruments, writing, time with friends), but I am also working a full time job with an 1+ hour commute each way. My time is so limited, and I am still just beginning to be able to budget, cook - take care of those necessary things.

I just came from mass where the homilist wisely advised us all to remember that God comes not to an alternate, imagined version of us or of our lives, but to us in our brokenness and messiness, really and truly - he comes to us as we really are. So while wishful thinking can be damaging, I can honestly say: I wish my most formative years as a young person had been filled not by the internet and all those other means of escape I found and clung to, but by real, actual, meaningful things that would have gradually prepared me to live a full and beautiful life during a stage of life when I actually had the time and the leisure to discover and enjoy them more fully.

I am so thankful for where I am now, but unlike you, I do not remember a time before the internet or before my life was nearly consumed by it.

I am only just now really getting free, and it is in the way you describe - I am falling in love with the real, and permanence and presence is gradually displacing the ephemeral and dissociative illusion in which I feel I lost myself for so long.

One thing I've noticed in my own screen use, and in conversations with other dads about their screen use, is that screens are an easy choice because they are so flexible about time usage making them very amendable to constant interruptions. Which, at least with small kids in the mix, are just part of life.

Whenever I've tried reading a book or practicing a hobby around my 4 year old twins I just end up extremely frustrated because I'm generally not allowed to focus for more than 2-3 minutes. (And they usually play independently pretty well but there's always "daddy look look" or "where are my scissors?" or "can you cut this tricky part?") You never reach that "flow state". Meanwhile, the kids don't ACTUALLY take my full attention anymore.

I've tried audiobooks -- and fumbling for the pause constantly when kids run up and suddenly start talking. I've tried screen free mindfulness and being in the moment -- but I don't need 4+ hours of that every single day.

I think this is the biggest challenge for going screen free, figuring out how to fill our shattered attention with something that ISN'T screens.

Yes, things are better when I organise an outing and I've taken the kids to the beach or a (short) hike or a museum. But that's not exactly scalable -- most people aren't going to have the time/money/energy to do things like that 5+ days a week.

Maybe things change once kids are in school full time? And parents just need to suck it up for those five years? Maybe helping break screen addiction is another small reason for universal preschool?

Just some rambling thoughts from a stay at home dad who thinks about this stuff a lot and struggles with it