When I was 16, I spent a year as an exchange student on the island of Sardinia, Italy. I lived with a host family in a small town and attended a local high school where the only person who spoke English was the English teacher. Otherwise, I was completely steeped in Italian, every hour of the day.

It was both exhilarating and exhausting. For the first several weeks, I lived in a blur of incomprehension. I often felt like an idiot. People would say things, I’d stare blankly, and then they would try to say it differently, but I still couldn’t figure it out. Despite willing every neuron in my brain to ascribe meaning to some of the gibberish, it did not, and I could only shake my head and smile apologetically. Sometimes people were visibly annoyed by my inability to understand; others were patient, presumably realizing that I wasn’t an inept dolt, but just needed time for the words to sink in.

Then it happened. It started with single words, which would pop out of an otherwise nonsensical phrase and alert me to what was being discussed. For example, my host mother would say something unintelligible, but I’d catch the word “pranzo,” and figure out she was talking about lunch. Then maybe “alle due,” and I’d know it would be at 2 o’clock. “Pollo” meant we were having chicken. Even if I didn’t catch much else, there were tiny handholds to grasp and pull myself up out of the dark hole of ignorance.

A few days later, there were more words. Then short strings of words. Then I started to make sense of basic sentences amid a paragraph of rapid-fire Italian. “Mangiamo il pollo a pranzo alle due!” And eventually, about a month after I arrived, I was able to understand most of what was said to me, and respond.

I put in an enormous amount of effort to learn. I went to school six days a week (yes, the teens in my town attended high school on Saturdays) and sat through hours of rambling professors giving lectures on Italian literature, philosophy, art history, Latin, math, biology, and more. Once I got home, after il pranzo, I studied at my desk for hours, painstakingly translating every word of my homework using a green and white Collins dictionary that quickly became dog-eared, with pages falling out.

The effort paid off and, within months, I was fluent in Italian. I was still so young, effectively a sponge, and by the end of the year, I was dreaming in Italian and had switched over to writing in my journals in Italian. I often forgot the English words for things. There were a couple proud moments where, on the mainland, I was mistaken for a native speaker with a distinct Sardinian accent. I gave a keynote address at a national Rotary conference in Naples. It got to the point where, if I heard English being spoken by tourists, I’d snap to attention at the strange, harsh sound of it before fully understanding what was being said. I always walked away without engaging; I didn’t want to speak English anymore.

The Gift of Immersion

Alas, those days are long gone. Looking back, 20 years later, it is hard to believe I was once so proficient in Italian. But I also recognize that the most critical component of my linguistic success that year was the fact that I was completely cut off from English. I experienced total immersion in a language with minimal disruption from my mother tongue. I don’t even know how an exchange student could accomplish that nowadays, thanks to the Internet.

When my exchange took place in the early 2000s, I did have an email address, but it was used only for transactional communication. I had MSN Messenger that I used a handful of times to message with friends back home, but that quickly fizzled out. I spoke to my parents on the phone every Sunday afternoon for one hour, but otherwise we wrote letters—copious quantities of letters—which now gather dust in a box in my basement. Apart from that, and short conversations with the high school English teacher, Italian took over my entire brain and being.

That disconnection was hard, even painful at times. I felt intense homesickness for weeks. I longed for my friends back home. I missed family vacations and my uncle’s funeral. But there was no other way for it to be. I had chosen to give up everything familiar for the life-expanding experience of a student exchange—and it was the right choice to make. I am so happy I did it.

An End of Absence

Now, my oldest son talks about wanting to do the same Rotary exchange program in a year or two. I am thrilled and support his idea wholeheartedly, but I can’t help but wonder, how will it be? I feel a bit sorry for him having to do an exchange in an era where communication is almost too convenient. He doesn’t have a smartphone now, but he might by 17, and I worry that a constant drip of contact with Canada might dilute his experience of another culture.

The Internet has given us many wonderful things, but it has destroyed the possibility of true absence. Physical and mental presence have splintered in an eerie way. It used to be assumed that wherever your body was, so was your mind (for the most part), but that is no longer the case. It is now possible to leave a place and still know everything that’s going on there in real time, and to be physically present in another place without really existing attentively within it. It’s astonishing when you stop to think about it.

It must be so easy now for exchange students to escape the discomfort and awkwardness of engaging with a foreign culture by escaping to their phones and social media feeds. I certainly would have done it, had it been an option; but it wasn’t, so I had to make do with writing letters, accepting profound solitude, and practicing more Italian. Over time, by forging ahead through that crucible of adaptation, I gained lifelong friends, cultural awareness, and a whole new language.

Optimized Learning

I suspect it is much harder to learn a language when the critical process of absorption is interrupted by snippets of your mother tongue via text, social media, YouTube videos, and more. It is so easy to whip out a phone, punch in what someone is saying, and immediately comprehend the meaning—except that eliminating the mental friction required to decipher new vocabulary is not conducive to learning! A translation app will not imprint a word on one’s brain as permanently as looking it up in a dictionary, repeating it, practicing it, and copying it down in a notebook for evening practice, as I did.

This is all speculation, based on my own experience, but I do not think I could have learned Italian as well as I did at the time if I’d had access to the technology that exists today.

I have no doubt that my son will do well on exchange, no matter what. Nor do I want to be a backward-looking Luddite who wishes things could be like they were “back in the old days.” But there’s something to be said for recognizing what has been lost. Sometimes a lament for what once was can provide useful perspective.

If my son moves abroad, I will try not to communicate with him on too regular a basis, so as not to disrupt the important connections he needs to form in his new home. I will strive to think of it as an extension of the parenting philosophy I already embrace, which is to promote healthy, natural independence. It won’t be easy, but easy isn’t the point. The point is personal growth.

You Might Also Like:

Why I Don’t Homeschool

A Defense of Rural Dwellers

Consider the Washing Machine

Upcoming Talk:

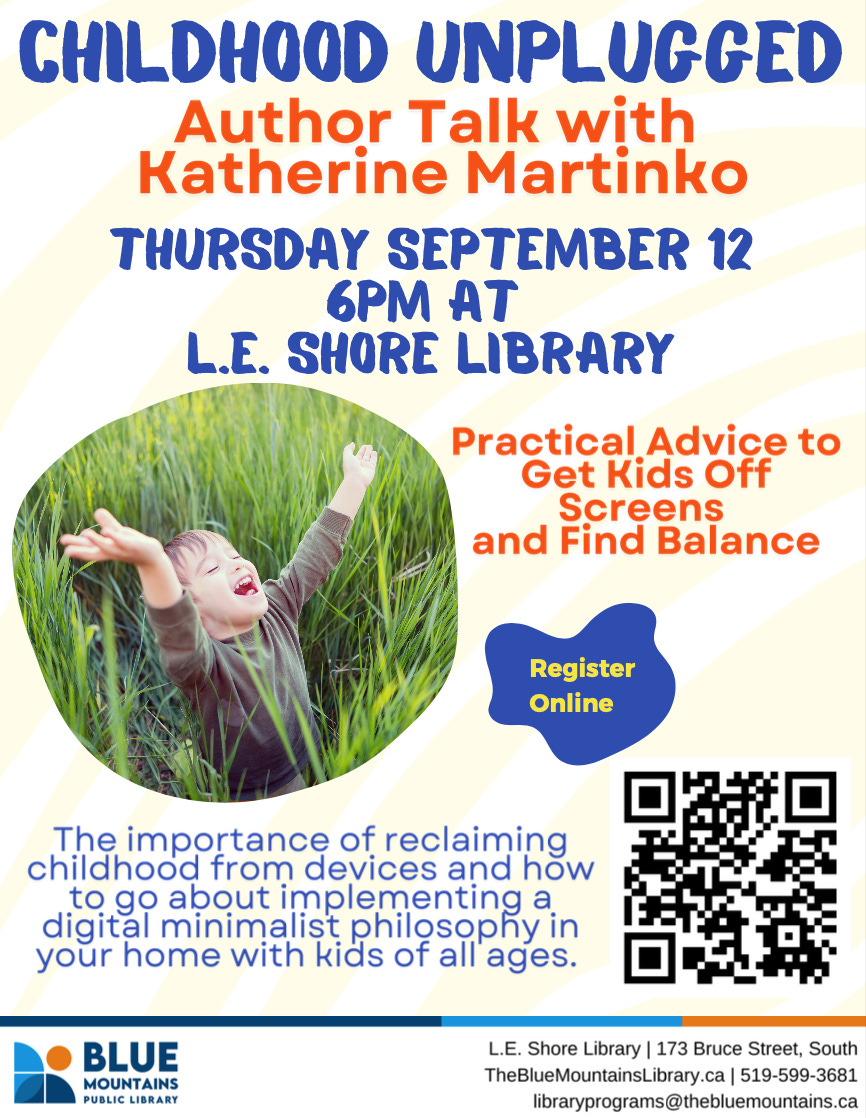

I will be giving a presentation at L.E. Shore Library in Thornbury, ON, on September 12, if you happen to live in the area. Come on out!

Note to Subscribers:

Thank you so much for reading and subscribing! The Analog Family is an entirely reader-supported newsletter, a true labour of love that I squeeze into my week around full-time work and raising three busy sons. You can help keep it going by becoming a paid subscriber. It makes a tremendous difference.

lol I feel slightly called out, reading this English article on a Munich subway as it takes me to my apartment here in Germany. You’re totally right that it’s hard to learn a language when you are so tethered to your native language on your phone! I’m so happy you had that wonderful experience as a teen. Sounds amazing!

I had an identical experience living in Japan in the early 2000s. No one spoke any English at all, and the only contact I had with my family was email that I had to travel across town to be able to send. I remember reading my dictionary and flashcards in my bedroom at night, and then venturing out to try to make small conversation during the day. Venturing around Tokyo’s scramble crossing, being exposed to sushi and red bean and other unfamiliar foods, it was a truly life-changing experience, and I often think about how that might have been the last time where you could travel in that way without smart phones!