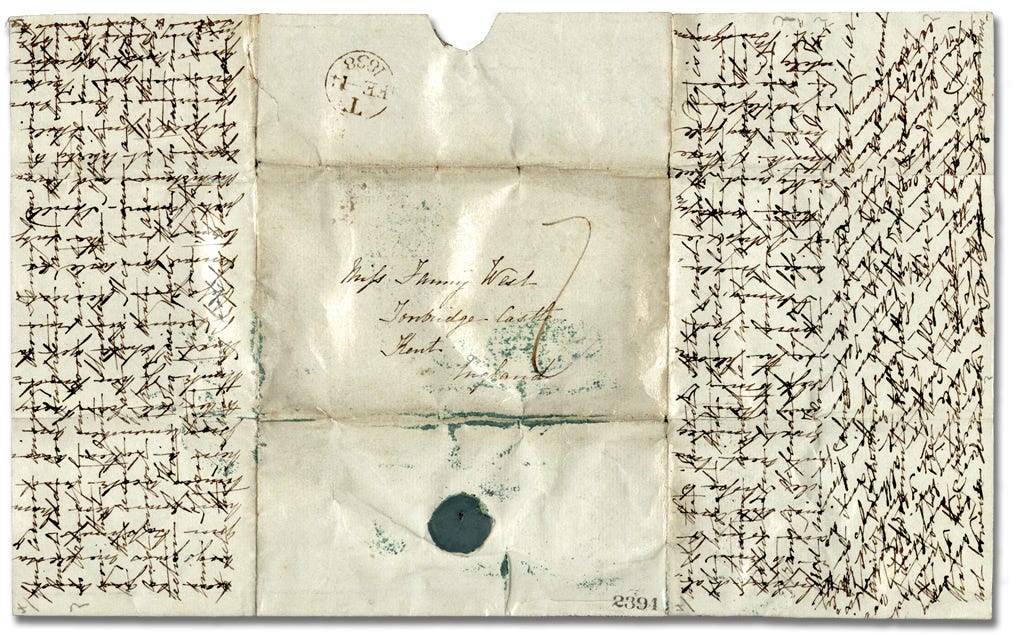

When I was a child, I saw an old handwritten letter sent by a settler family in Upper Canada back to England, sometime in the 1800s. It was an example of a “crossed” letter, with a full page of text written conventionally, then the page was turned 90 degrees and filled with another full page of text. All the lines overlapped, which, to my inexperienced eye, made it look indecipherable; but if you could figure it out, you’d get twice the amount of information.

An avid letter-writer myself, this crossed letter fascinated me. I tried to write one to my grandma, unsuccessfully. I’ve since learned that it was fairly common practice at the time, as it saved money on expensive postage and paper, which was hard to get in the colonies. I imagined a family sitting around a table, illuminated by candlelight, having finished a day of hard labour, deciding what to tell their relatives overseas about their new foreign life. Where would you even start? Having limited space and opportunity to communicate forces one to think long and hard about what deserves inclusion and what does not.

I thought a lot about how much was left unsaid. There would come a point when a settler family would simply have to accept that their relatives would never know or comprehend significant swaths of their new life, that it could not be contained or explained in limited words, that huge chunks of time would pass between letters and things that once seemed important had faded into the background. At a certain point, you would just have to accept that your lives had diverged from those of loved ones back home, and no number of meticulous crossed letters would be sufficient to bridge that gap.

Today, we inhabit a wholly different kind of world, one that is flooded with communication. No longer do we need to choose our words with care or consider what’s worth saying. We just say it all, because we can.

We talk easily and incessantly with friends, family, and strangers, sending near-constant text messages, emails, direct messages or comments on social media platforms, and making calls by phone, FaceTime, or Zoom. Not only that, but a torrent of photos is sent or posted online to illustrate one’s private life. Sometimes it feels like we inhabit a snow globe of information. It’s pouring down on us, inundating and accumulating, to a point of oversaturation where nothing soaks in anymore.

More times than I can count, I have carried on full-day texting conversations with people, where a conversation is drawn out for hours because of the delay between messages or because random thoughts keep popping into our minds. By the end of the day, I’m not quite sure what has been said (I could go back and read it all, but why?), apart from a vague sense that I have struggled to focus on work and wasted a great deal of time. It does not feel productive or satisfying in the way that meaningful communication should.

Overwhelmed by a compulsion to share, nothing is special anymore. And when everything has already been shared, there is nothing left to talk about when you finally see someone in real life. You feel a sense of already being caught up on what’s happening—except that what is portrayed or conveyed online rarely aligns with reality, so you can’t assume you actually know what is going on in anyone’s life.

I notice this in communication with my husband. If we message throughout the workday, I already know the answer to the question, “How was your day?”, when we see each other at dinner, and there is less curiosity about what we each did. But when he leaves for a four-day canoe trip in the wilderness, as he did this past weekend, with no cell service in northern Algonquin Park, I look forward to hearing the details of his adventure. There’s so much to talk about!

Pondering this, I wonder if humans are innately wired to want to share every detail of their lives with the broader world or if the technology made us this way. I lean more toward the latter. The digital devices we all own exploit a natural instinct to connect with others, distorting it and turning us into sort of sad, desperate versions of ourselves who can’t get enough of this thing we know we need, but certainly not at this level of intensity.

A phrase that has begun echoing in my head recently is, “Save it.” Don’t be so quick to offer up that information to the maw of the device. Instead, hold onto it. Keep it close. Contemplate it. Consider whether the world needs to hear. Sometimes I ask myself the now-famous set of questions that was first outlined by Craig Ferguson: “Does it need to be said? Does it need to be said by me? Does it need to be said by me now?” And often, the answer is no.

I am texting less these days, preferring to save up information for in-person encounters. Not only does it ensure we have interesting things to talk about, but it also weeds out the superfluous background noise that might otherwise get in the way of forming deeper thoughts.

I would hate to return to a time when paper and postage was so expensive I had to write crossed letters to communicate with my family, but there is undeniable value in giving thought to what’s worth saying and what is not. Just because I can say it does not mean I should. Perhaps we should strive to keep more to ourselves.

You Might Also Like:

A Small Reminder:

I am able to write this newsletter twice a week, thanks to generous readers who enjoy my words enough to sign up for a paid subscription! Substack is not exactly a money-maker, if I’m honest, but every bit helps—perhaps most of all by validating my belief that I’m on the right track with this quest to reclaim childhood from digital devices. Here’s a motivating message from one subscriber who recently upgraded to paid:

Katherine, your observations ring true over and over, but this one compelled me to comment! I tried this during Lent of this year, a time when Christians have often given something up in order to focus more on God. I've tried all manner of tech-fasts over the years to try to break my habits, but this one felt different because it affected other people. I didn't keep it perfectly; I still texted here and there, but it sure cut back on the drawn-out exchanges, and I think it started to characterize me as someone who doesn't immediately reply, which I found to be a good thing. I had hoped to replace my texting with more meaningful communication -- phone calls, letters -- but I didn't do that nearly to the extent I had hoped. I have this ambition to single-handedly save the US Postal Service with my prolific letter-writing, but that has yet to materialize, ha! Your reflection today, though, made me consider the long-distance relationship I have with my extended family, who all live halfway across the US from me. Generally I feel some pity for myself when our nuclear family experiences some hardship (currently, pneumonia and a newborn), but you made me reconsider that. I expect my family to use all the technology at their disposal to ease my trial. But, in the grand scheme of things, that's not really theirs to do. We made the choice to move here, and in ages past, we would have muscled through (probably with more childhood fatalities from illness, though, ugh). As a Christian, I believe in God's providence, so I'm trying not to expect my family and technology to care for me in a way that is not entirely in their hands.

I looove love love this idea! I have had similar thoughts about this before, but it’s so hard to opt out and feel like the world moves on without you. I don’t mind opting out of news cycles and social media. But texting with loved ones? That’s a hard one. But if it clears space for slower, deeper, and more meaningful communication than sign me up! I also think that stepping back from constant communication within our nuclear families and larger families requires a level of trust as communication will shift and begin to look different. Thank you, as always, for sharing!!! ❤️