It has been a spectacular news week in terms of limiting kids’ access to digital media. Every time I opened my computer, there was another headline from a different country about real or proposed steps to get kids off screens. In all the years, I’ve been covering this topic, I have never seen anything quite like it. So, what’s been going on?

In France:

An experimental “pause numerique”, or digital pause, has been implemented at 180 middle schools, attended by students between the ages of 11 and 15. It is a pilot project that requires students to hand in their phones upon arrival at school, as opposed to simply turning them off, which is what has been required in French elementary and middle schools since 2018. Most high schools already prohibit phone use, and devices are not allowed during extracurricular activities and school trips.

While French schools already have a good handle on mobile devices, they’re not being complacent. Bruno Bobkiewicz, general secretary of France’s union of school principals, said that the 2018 ban had been fairly well enforced and the “use of mobile phones in middle schools is very low today.” That is why “we have the means to act.”

This new trial affects more than 50,000 students. According to France24, it is part of the government’s effort to improve school climate; reduce instances of violence, including online harassment and dissemination of violent images; improve student performance by boosting the ability to concentrate and acquire knowledge; and raise students’ awareness of the “rational use of digital tools.” If deemed successful, the pilot project will be implemented nationwide in January 2025.

In Australia:

The country says it plans to set a minimum age for kids to use social media, likely between 14 and 16. According to Reuters, prime minister Anthony Albanese said his government would run “an age verification trial before introducing age minimum laws for social media this year.” This announcement was made following a parliamentary inquiry into the negative effects of social media on mental health.

Albanese wrote an opinion piece on September 11 that outlined his goals:

“I want young Australians to grow up playing outside with their friends, on the footy field, in the swimming pool, trying every sport that grabs their interest, discovering music and art, being confident and happy in the classroom and at home. Gaining and growing from real experiences, with real people.”

He recognized that parents have the option of banning smartphones and social media for their kids, but that this is easier said than done. “[Parents] are up against the powerful force of peer pressure, and no one wants to make their child the odd one out. Setting a new national minimum age for social media also sets a new community standard. It takes pressure off parents and teachers and backs them with the authority of government and the law.”

In Finland:

Finland has long had a reputation for its stellar academic standards, but these have been slipping recently. One dire report in 2023 said that national learning outcomes were in “rapid decline.” After years of issuing free laptops to students as young as 11, some schools in Finland are wondering if screen time might not be so beneficial after all.

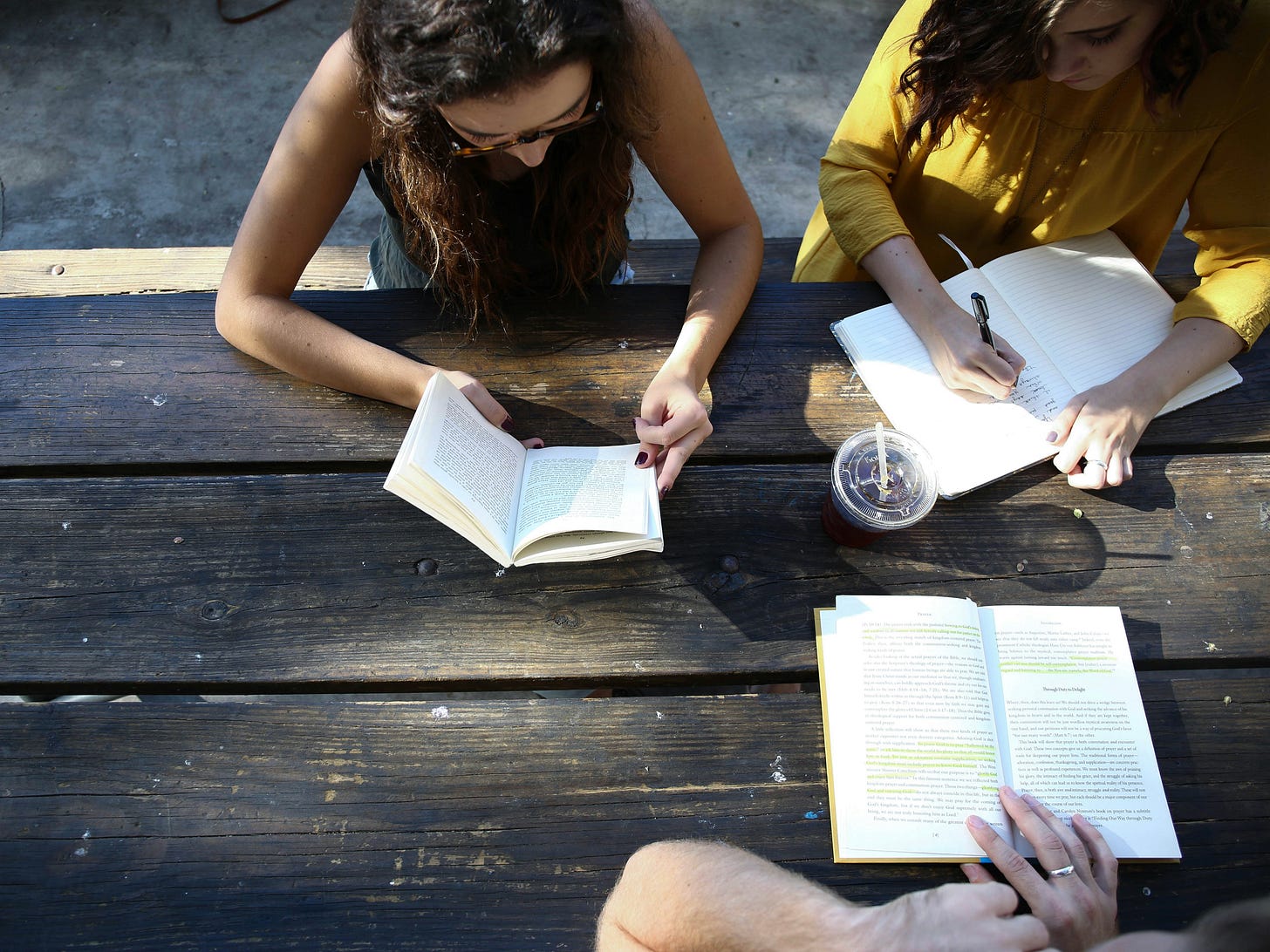

In response, schools in the town of Riihimaki, with a population of 30,000, have decided to go back to basics, giving students physical books, pencils, and paper once again. One English teacher, Maija Kaunonen, told Reuters that using digital devices in the classroom was too distracting:

“Most students just did the exercises as quick as they could so they could then move on to playing games and chatting on social media. And it took them no time at all to change tabs in the browser. So when the teacher came round to them, they could say, ‘Yes, I was doing this exercise’.”

Now, things are different. Even students are saying they’re more focused without devices. Two eighth-graders said, “Reading, for one, is much easier and I can read much faster from books,” and “If you have to do homework late at night, it’s easier to go to sleep when you haven’t just been looking at a device.”

In England:

One of the country’s biggest academy school trusts has moved to ban mobile devices. Ormiston Academies Trust told the BBC it was “phasing out access to smartphones for around 35,000 pupils” at 42 state schools in an effort to combat the negative mental health impacts of too much screen time.

Several of the schools had already tested limiting phones, to great success. Apparently, these efforts were “really successful” and “popular” with students and parents. Said Tom Rees, Ormiston’s chief executive:

“Learning can’t happen without attention. A lot of this is about a battle for attention, a battle for focus and concentration. It’s not just about having your phone out and using it, it’s the mere presence of the phone… An increasing distraction is catastrophic for the process of learning, and that’s true both at school and at home.”

Earlier efforts in England to limit phones in schools were non-binding, leaving it up to school administrators to decide how they wanted to implement rules; but this has been largely ineffective.

Meanwhile, in Ontario:

Our laughably feeble phone “ban” marches on. I find it downright funny that it’s called a ban, when students in grade 7-12 can still keep their phones on their body throughout the day, but are not supposed to look at them unless a teacher gives permission. They can still go to the bathroom with their phone, look at it in the halls and during lunch. How can that be considered a ban?

“It’s no different than it was before,” a teacher friend told me this week. “It’s still up to each teacher to decide how to let kids use their devices, and that varies a lot, as you can imagine.”

And my oldest son, in high school, reported that the rules are already starting to slip in classrooms, since the beginning of classes last week. “I think the teachers are getting tired already,” he said.

Overall Hopefulness

Globally, however, it is exciting to see this digital media debate gaining traction and some real efforts being made to tackle the associated problems. It represents a profound shift in awareness, and it is absolutely critical if we stand a chance of giving kids back their experience of childhood—with all the boredom, creativity, free play, and awkward social interactions that it entails.

A Small Reminder:

I am able to write this newsletter twice a week, thanks to generous readers who enjoy my words enough to sign up for a paid subscription! Substack is not exactly a money-maker, if I’m honest, but every bit helps—perhaps most of all by validating my belief that I’m on the right track with this quest to reclaim childhood from digital devices. And maybe someday I’ll be able to quit my other two jobs and do this full-time, which would be absolutely lovely…

You Might Also Like:

In the News:

Please check out my latest column for the Globe and Mail, Canada’s biggest newspaper: Want kids to be safe? Then ditch their smartphones (paywall, Sept. 11)

Our middle school has an “away for the day” philosophy: phones in lockers all day, and strong punishment for failing to comply. While likely just correlated, my daughter dumps her dumb phone at the front table and forgets to charge it most days.

It seems we need to get to that day when administrators find the courage to completely ban (not limit) smart phones and personal computers in schools for students and for teachers/staff. The research is firm and conclusive that smart phones the CAUSE of and not a correlation for depression, alienation, loneliness, low self esteem, suicidal ideation and more among children and teens. Teachers and parents cannot be tasked with doing this on their own. It doesn’t work that way. It has to an all-in remedy that’s strictly enforced. This must start with administrators educating their school communities on the harmful effects of social media freely accessed by children and even adults and then implementing a plan that’s effective and easily implemented.

This is not an us-them problem (kids-adults). We are all in this together and we are all diminished by social media platforms and their algorithms that so easily and powerfully influence us.