My son has to write an essay on Romeo and Juliet for his grade 10 English class. The teacher insists that every stage of the essay development be written by hand, from the basic outline with thesis statement, supporting arguments, and various proofs and citations, to the full-length rough copy. Students must show their work along the way and are not allowed to approach their school-issued laptop until the final version is ready to type.

I don’t know if his teacher has taken this delightfully old-fashioned approach because of a recent incident where a student submitted an essay written entirely by AI—and was caught, of course. I do wonder if some teachers might choose to tackle the threat of AI by going back to pen and paper, an amusing reversal after years of pushing technology in the classroom. One might think of it as “revenge of the analog.”

Nevertheless, I am pleased. There is nothing quite like engaging with handwriting to get one’s thoughts moving. I often brainstorm by hand, scribbling in large Moleskine cahiers with my favourite pens from Muji or my beloved metal Kuru Toga mechanical pencil with the revolving lead that always stays sharp. Only once I have a lengthy list of points do I pull them together into a typed Word document.

I don’t do this for every piece I write, but after a decade of writing over 4,000 news articles, I have learned that taking the time to sketch out a piece by hand, and really think it through, usually saves time when it comes to the actual writing.

It turns out, I’m not alone. In a 2013 article for Scientific American called “The Science of Handwriting,” Brandon Keim suggested that “perhaps hand-formed letters, inscribed more deeply in our mind, are building blocks for sturdier mental architectures.”

He cited Christina Haas, a professor at the University of Minnesota and editor of a journal called Written Communication. Haas found that her students did a better job at planning their writing when working by hand, rather than on a computer. She said her students said, over and over, that they couldn’t get a sense of their text when working on the computer.

Haas went on to wonder, “How can it be that the tool you use can influence what's happening in your brain?” She told Keim, “I know this sounds simple, but it led me to the insight that people weren’t talking about—it’s the human body that intervenes between the tool and the brain.”

We forget that our hands are a key part of that intervention between tool and brain, that they have allowed us to achieve “exquisite versatility and precision,” to craft tools and refine skills and even develop gestures that are thought to have helped language evolve. Virginia Berninger, an education psychologist at the University of Washington, said, “We use our hands to access our thoughts.”

When we turn to computers, that intimate bond of communication between hand and mind becomes disrupted. Yes, we type with our hands, but it is a different kind of interaction. Within months of learning how to type properly, it becomes automatic, mindless, an extension of one’s thoughts.

Norwegian literacy professor Anne Mangen put it most beautifully when she explained that handwriting “unifies hand, eye, and attention at a single point in space and time. Typing on a keyboard, which Mangen calls ‘the abstraction of inscription,’ breaks the unity.”

This made me recall my first-year political science class, when I took notes on a laptop and found that I could type at the same speed that the professor spoke. At first, I thought this was great; I ended up with fully transcribed lectures. But then, I realized I had failed to engage in the critical process of listening attentively and distilling relevant information, so I ditched my laptop and switched to handwritten notes, which helped me greatly with retention.

Some of the most effective academic tools are analog. There was an interesting roundup of the best ways to study, with psychologists looking at 700 scientific articles on the 10 most commonly used learning techniques. Researchers identified two clear winners—self-testing, or doing practice tests outside of class to test recall or answer sample questions; and distributed practice, or spreading study efforts over time to improve retention. Neither of these (nor any of the others) requires the use of any digital media.

I am not entirely opposed to technology in the classroom; it is useful to have certain tools, but if we ditch all the analog ones en masse in favor of digital, we risk losing key experiences along the way, like how satisfying it feels to sit down, brainstorm by hand, and shape arguments with a pencil on paper—refining that “mental architecture,” like Keim said, to build a solid intellectual structure.

I do not expect most of my son’s future high school teachers to insist on handwritten drafts, but I am glad this one has. It is a valuable and satisfying exercise, and I hope it makes a lasting impression on him.

You Might Also Like:

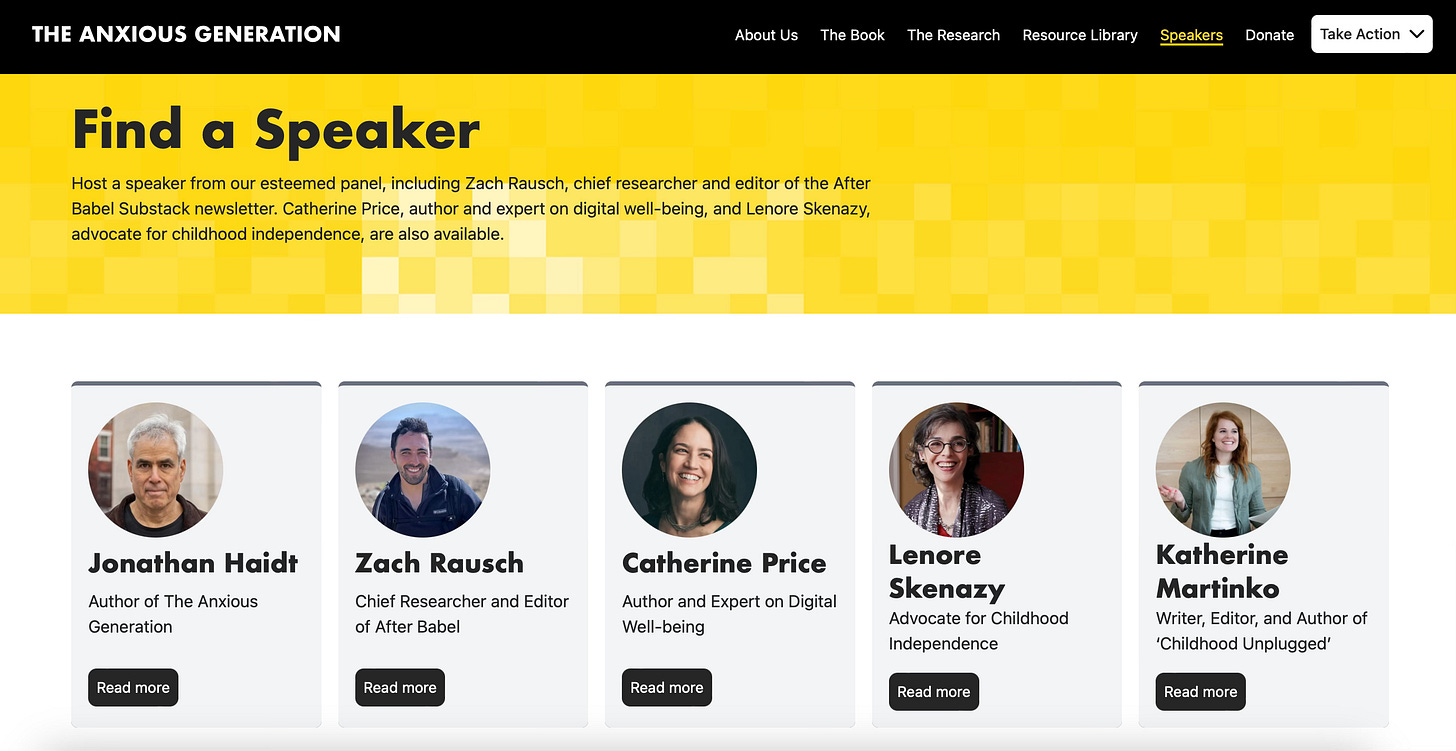

The Anxious Generation: I’ve Joined the Team!

If you’re looking for a speaker on digital minimalism, I’m now on the roster with some other incredible writers and thinkers. Please reach out if you’re interested in booking a talk.

A Small Reminder:

I am able to write this newsletter twice a week, thanks to generous readers who enjoy my words enough to sign up for a paid subscription! Substack is not exactly a money-maker, if I’m honest, but every bit helps—perhaps most of all by validating my belief that I’m on the right track with this quest to reclaim childhood from digital devices. Here’s a motivating message from one subscriber who recently upgraded to paid:

Maria Montessori stated almost a hundred years ago, “The hand is the instrument of intelligence. The child needs to manipulate objects and to gain experience by touching and handling.” Although, considering the comment below, fortunately there are other tools that can assist children and adults who need assistive solutions, but many don't.

I had a history professor in college who would fill the chalk board with handwritten notes before each class. She told us on day one that the only way to succeed in her class would be to copy the notes as she lectured. Her expectations were high, but clear, and I copied probably 4 pages of notes per class. Looking back, I’m so grateful for the time she took to write those notes on the board and her commitment to meaningful learning.