If you have ever wondered how a vocal proponent of digital minimalism manages screen time in her own home, now is your chance to see what goes on behind the scenes at my house!

My three sons are 10, 13, and 15, spanning elementary, middle, and high school, so I am in the thick of it, witnessing firsthand how the technological takeover of childhood is affecting their friends, peers, and broader generation, while also dealing with their strong opinions about not having smartphones when most of their friends do.

I am not anti-tech. I think modern technology is incredible. It has enabled my entire career as a writer, and I would not want to live in a world where laptops, high-speed Wi-Fi, the Internet, and FaceTime do not exist. But this tech is a powerful tool, not a toy, and it should not be our primary form of entertainment or engagement with the world. It must be treated with caution and respect, and we should always ask ourselves what is being lost during our incessant quest for convenience and speed.

Over time, I have come up with the following rules to guide my family’s screen time. These are not perfect; they are a work in progress and, as you can imagine, are being constantly challenged, revisited, and discussed, but they help to define an overarching philosophy that shapes our family life.

No Smartphones Before 16 (at minimum)

Owning a smartphone should be on par with getting a driver’s license in terms of the maturity required to operate one. This comparison comes from Dr. Jean Twenge, author of iGen and Generations, who said in an interview that she wouldn’t give smartphones to her own three daughters until at least 16. We don’t put 10- or 12-year-olds behind the wheels of cars because we understand that they could do significant harm to themselves and others; they’re just not ready for it yet. Smartphones are like that, in Twenge’s opinion. Kids need a certain baseline of maturity before they should be given such tools.

Twenge’s recommendation is noticeably stricter than the first of Jonathan Haidt’s four norms, laid out in The Anxious Generation, where he recommends waiting until 14 or the start of high school. As he explained to me once, waiting longer is preferable, but he’s trying to be realistic about what parents will do—and 14 is already much later than when most kids are getting their first smartphone.

My oldest will be 16 this summer and, quite frankly, I’m uncomfortable at the thought of handing over a smartphone. He is a mature and responsible kid, but I struggle to see what the point would be, considering all the workarounds for communication we’ve already established, our unique geographic circumstances (our house is centrally located, very close to his friends and school and extracurricular activities), and the fact that he can’t be on social media anyway. He, of course, wants one for social status more than anything. So, that’s something I’m still mulling over. We don’t have good basic phone options here in Canada, not nearly as many as in the U.S.

We do have a landline, which sounds archaic, but it is surprisingly great. It’s from a company called Ooma; it’s VoIP and only costs $6/month. It means the kids can call their friends and relatives whenever they want, and I can reach them if I’m out and they’re at home. I know several families that have reintroduced landlines. It’s probably too soon to say they’re making a comeback, but don’t overlook this option.

I let my kids borrow my phone to send texts or look things up occasionally, and I’ve heard of some families that keep a shared phone on hand that kids can borrow when they need to take a cellphone somewhere, but don’t need one all the time.

No Social Media Before 18

The evidence is abundant that social media is no place for kids. It’s a rabbit hole that, in a best-case scenario, offers shallow content that entertains and amuses, and in a worst-case scenario, exposes kids to a dark, ugly world full of disturbingly violent, sexual, or overly mature images, videos, and interactions with strangers. At the very least, it pulls kids out of the present and their immediate surroundings, diminishing opportunities for interaction with the people who care about them most.

If the former Surgeon General of the U.S., Dr. Vivek Murthy, was worried enough to issue an official advisory against social media, citing a “profound risk of harm” and saying “we do not have adequate evidence to determine whether or not social media is safe for our kids,” then we probably shouldn’t give it to them.

In an op-ed for the New York Times, Murthy said, “Why have we failed to respond to the harms of social media when they are no less urgent or widespread than the harms posed by unsafe cars, planes, or food?” None of us questions strict regulation in those other industries he mentions, so why is social media still such a free-for-all, particularly for our most vulnerable demographic?

It is true that restricting access to social media until 18 will mean that children and adolescents miss out on many things happening online—but just think how much they will miss out on if they spend upwards of 5 hours a day on it, which is the current daily average for teens.

My kids may choose to get social media once they turn 18—just like I did—but at least they’ll be well past puberty at that point (the most harmful ages at which a kid can use social media is 11-13 for girls and 14-15 for boys). Hopefully, they’ll be less impulsive, more self-controlled and self-confident, and possessing other well-established interests that will deter them from squandering excessive amounts of time on the platforms.

The goal of delaying is not just to protect them, but also to give them a chance to develop a baseline understanding that offline life is valuable, good, and worthy of pursuit.

Read: Why I’m Skeptical About Warning Labels for Social Media

Computers for Communication

We have an Apple desktop computer that sits in a common area of our home, and that’s where my kids sit down each day to check iMessage. They receive and send a flurry of texts with their friends, in both individual and group chats, and they get more than their fair share of silly memes and videos—but it all stays on the computer. When they log off and step away, the messages do not travel in their pocket, accessible everywhere and all the time. There is friction that exists between the desire to check messages and the convenience of doing so.

Apps like Signal and WhatsApp can be used from a desktop computer, too, which could be another way for kids to be able to have independent communication with friends. I’m all for independence; I don’t want to be the go-between when it comes to them making plans with friends—I outgrew the role of playdate manager nearly 10 years ago—but giving them the tools to do it does not mean handing over the most advanced form of technology we have, with all its associated risks and distractions.

My oldest has a laptop computer that was issued by his public high school in grade 9, something I protested initially but was told by the principal that there was no workaround unless I wanted to pull him out of the system completely. I chose not to fight that battle further, and so he uses it for homework, research, and email. It hasn’t been a problem over the past two years. Laptops are known to be less addictive than touchscreen devices, so it’s preferable to give a kid one of those than, say, a tablet.

Read: Interactive vs. Passive Screen Time: What’s Worse?

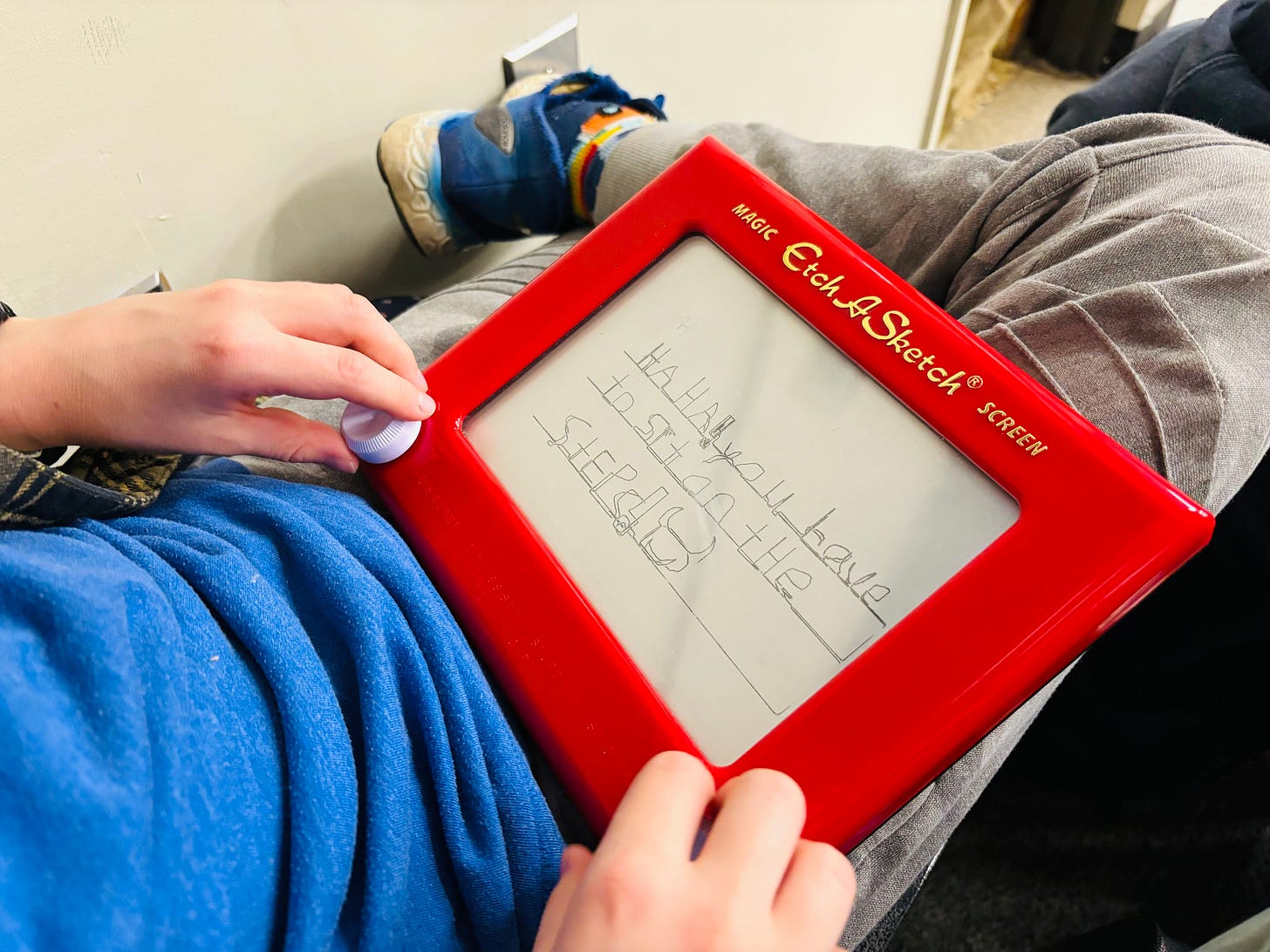

Screen Time Is Unscheduled

My kids still get “fun” screen time, usually in the form of watching movies using our Netflix account on a laptop, but it happens sporadically, spontaneously, not on any kind of schedule. It happens on lazy weekend nights when not much else is going on, or when I just really need a break, or if someone’s sick, or if the weather is terrible. I have no problem with this.

Not all screen time is created equal. “Good” screen time is any kind of long story with a narrative arc, a moral message, character development, watched on a large(r) screen, ideally with someone else—in other words, a high-quality movie. “Bad” screen is fragmented time, like short, fast-moving video clips watched in isolation on a touchscreen device, scrolled through quickly as soon as anything gets slightly boring—in other words, YouTube shorts and TikTok reels. Given the choice between a movie or short-form videos, always go for the movie.

When my kids go to other people’s houses, I do not impose my unconventional philosophy. That would feel rude and pretentious, considering that another parent is generously hosting my child, so I don’t say anything. I could also choose not to send them. But usually they go, and they play video games and watch YouTube videos for hours—and they love it—but then they come home with a sense of relief that we do things differently in our own home.

I don’t love this, but I also don’t mind it. I think that occasional exposure to the games, characters, and memes that dominate the popular culture of their generation at this point in time is not a bad thing; it makes them feel a bit more relevant and connected, not totally out of the loop, but the fact that we don’t have it in our house creates a healthy buffer.

What About Music?

Another ‘rule’ is letting them use an old iPhone XR (with a broken screen) for music, which they love. They sign in to my Spotify account, make playlists, and listen while doing the dishes or working out in the garage. The phone doesn’t go anywhere else in the house. Yes, there’s the possibility of them doing other things on that phone, but our Wi-Fi signal doesn’t reach the garage, so I know that whenever they’re out there, they can only use downloaded music.

Not Perfect, but Good Enough

As mentioned, these are a work in progress. I’m learning as I go, as my kids get older, as new questions and challenges arise. We parents do not have the benefit of retrospection when it comes to handling this tech because we did not have it growing up; we are all trying to figure it out for the first time, trying to do what’s best for our kids, while fighting the temptation for it to take over our own lives, too.

Guidelines can help. When they’re laid out clearly for kids, there is less arguing and pushback. They understand what’s expected, and so do you. It helps to reclaim a sense of authority on the part of the parent, and greater peace within the household.

You Might Also Like:

Have You Read My Book?

Childhood Unplugged: Practical Advice to Get Kids Off Screens and Find Balance is available in paperback, PDF, or audiobook. If you love it, as many other readers have (it’s got a 4.9-star rating!), consider leaving a review on Amazon, which my publisher tells me is a huge help for boosting sales and visibility. If you’d like to learn more about my work, please check out my website.

A Small Reminder:

I am able to write this newsletter twice a week and keep it open to the general public, thanks to generous readers who enjoy my words enough to sign up for a paid subscription! It’s entirely a labour of love and it takes a LOT of time and effort to do. Paid subscribers are a sign that I’m on the right track.

I am in the thick, too, with a 14 year old finishing 8th grade (I also have an 11 year old and a 7 year old). I must be a little older than you because I didn't have social media until I was in my late 20s, which is when I started using Facebook (which I no longer use except for minimal business purposes). However, even by my mid-late 20s, people began to use blackberries. I found them to be so annoying. We would be trying to talk, and the person would be glued to whatever was happening on the phone. Then smartphones took it one step further. I was a little later to the smartphone world getting my first in 2014-2015, but I don't use social media, so for me, it's little more than messaging, maps, music, and podcasts, and most of the time sits unused. My husband and I were old enough to see the dangers in devices and social media before we started having kids in our 30s, and we knew from the beginning that screen time would be as minimal as possible. As the years have passed, we have only grown more militant about this, particularly as we learn that college students are unable to read entire books or watch movies without looking at their devices. In a generation, we have re-wired children's brains, and parents just take it as: this is the way things are now. For my son, our restrictions have been difficult. His entire baseball team has had phones for several years. We finally relented this spring when he turned 14. He got my old iphone 7, and I upgraded. I have the phone basically locked down with screen time, and I removed the apps like safari, as well as access to the app store. He can listen to music, text with his friends, and take photos. It does give him freedom and makes him feel a little less left-out, but he still pressures me for more. I get that at 14 kids do not want to feel different or left-out. I also get that he thinks our house is boring because we don't have video games; the kids don't have computers in their rooms; and they have never had their own ipads. On the other hand, he was able to read Tale of Two Cities in the fall of 8th grade and my kids can sit through multi-hour dinners and hold conversations with adults. I'm not sure what will happen in the future or whether my kids will rebel against my rules. But I do hope that when they are in college and they are able to focus on their work and read entire books, they will look back and understand why we did what we did.

This is an excellent article, and somewhat reminiscent of my own childhood. I greatly appreciate your work, as I grew up in the first two decades of the twenty-first century with no smartphone. A flip phone is still my main method of communication, and I can always recognize others who were raised in a similar way. It is my hope that we digital selectives can create a culture based on these principles.