Sometimes, when I talk to parents about taking away their kids’ screens, they look at me in absolute horror, as if I’ve just asked them to embark on some kind of severe elimination diet or gruelling exercise regime.

“What are they supposed to do?” the parents ask.

It’s a fair question. The daily total screen time averages reveal a lifestyle that is grossly skewed toward online entertainment and away from real-life engagement. Tweens, aged 8-12, spend 5.5 hours a day on devices, and teens spend 8 hours, 40 minutes, on average—and that’s just scrolling, having “fun”, not doing homework or any necessary communication.

When you take that away, it leaves a gaping void. It is not surprising that children and adolescents—and their parents—struggle to know how to allocate their time and attention elsewhere. Many households feel overwhelmed, lost, aimless, perhaps even a wee bit bereft when screens are removed from the equation. It’s like a crutch has just been knocked over, and now they’re staggering, struggling to catch their balance without anything to grab onto.

That’s when I introduce the concept of a replacement phase, when the digital toys and activities are swapped out for real-life ones and kids are forced to (re)learn how to play on their own. It takes a while; independent creative play is a muscle that needs to be exercised in order to remain strong, and if it has been left to atrophy for years, it could take weeks or months before the child is able to do it again with ease.

There is also an adjustment period during which a child must “come down” neurologically from ongoing screen-based stimulation and reestablish a healthy emotional baseline. According to psychiatrist Dr. Victoria Dunckley, this could take as much as four weeks. This could be a rocky, emotional time for some families, who may, in extreme cases, have to grapple with the fact that their child has never learned to self-regulate emotionally without relying on a device. That’s a tough thing to learn after patterns have been established, but it's not impossible—and certainly necessary.

Today, I’d like to dig more deeply into what exactly kids can do with their time. Obviously, this changes based on a child’s age, environment, gender, access to siblings and other playmates, but generally, how does that void get filled? What is realistic to expect children to do with 5-9 extra hours that are suddenly added to their day?

Most of all, I want to emphasize that parents should not fear this. It is an adjustment, yes, but it is less scary than you might think.

Loose-Part Toys

Kids are embodied creatures; they need things to do. They have to use their bodies in a range of ways to develop fine and gross motor skills. You can buy or collect toys for them, ideally loose-part toys, which do not have a single predetermined function, but rather are open-ended toys that can be reinterpreted in whatever way a child wants. This interpretation will likely evolve based on the child’s mood, capability, the season, who their playmates are, and more.

For young kids, this could be cardboard boxes, a bucket and shovel in a sandbox, sticks, rope, rocks, leaves, beads, fabric, measuring cups and spoons, containers with lids, pom-poms, etc. For older kids, it could be yarn, costumes, building materials and construction supplies, art and craft supplies, jewellery-making kits, modelling clay, paints, stamps and ink pads, theatre props, etc. Sporting gear like balls, a slack line, and a trampoline are great fun, too.

Resist the urge to view this as clutter. Part of encouraging analog play is accepting that there will be mess and visual chaos at times. If you rush to clean it up, you deprive your kid of the opportunity to get back into a project again, so try to let it be (within reason!).

Organized Activities

Some families gravitate toward organized activities to fill the void that is left by fewer screens. This can be a great solution, as long as it doesn’t take over your life completely and start encroaching on mealtime, homework, bedtime, and even just quiet downtime.

My three boys play soccer from May till August, and it’s a frenzy of activity; at least two of them play every night, Monday to Thursday, with occasional extra weekend practices or games. It’s tiring for me and my husband, but it keeps them busy.

A friend recently told me about how wonderful Scouting has been for her three kids. She said, “Everyone should get their kids in Scouts! It deals with everything, from getting them off screens to building resilience and teaching skills to letting them be bored.” One of my kids is in Air Cadets, which he initiated because he wants to be a pilot someday. It adds structure to his life and keeps him occupied for three hours every Tuesday night.

Reading

If play fills the active part of the void, then reading fills the quiet part. For those moments when your kids are off screens but not feeling like rambunctious play, then reading is what they can do. Again, this is a habit that must be cultivated. It’s what many of us did as kids, whether we read novels or comics or magazines, and there’s no reason why we can’t reestablish it as a normal, expected childhood behaviour. As I wrote last summer:

Without books, I struggle to imagine how you would keep kids entertained or engaged indoors when the weather is bad, or it’s dark in the evenings, or you’re in the car for hours, or you simply need silence in the home. There are only so many crafts you can do, but reading feels limitless.

Again, this takes upfront work on the part of the parent. You must insist that the child dedicate a few minutes a day to reading and then work up to longer chunks of time. You need to supply good-quality material that captures their attention, which requires research, gathering recommendations from reliable sources, picking up books from the library, or ordering them online. Ideally, you would read, too, modelling the same behaviour that you want them to emulate.

Play With Friends

Free play with other kids of mixed ages is developmental gold. Kids thrive on it. Having siblings make this a lot easier, but even that can get boring at times, which is why it helps to invite other kids over to play. Import playmates if you must, whether by organizing playdates or inviting neighbourhood kids to play or hosting cousins for multi-day visits. You can even hire a preteen to play with your child, while you remain present in the home, doing your own thing.

When my first child was just over a year old, I started a weekly childcare swap with a friend who had a son the same age. Both of us were finishing university degrees that year and needed time to focus. We each took the other’s kid for a full day per week, which was fantastic; our boys, neither of whom had siblings yet, benefited from having a built-in playmate for two days a week, and neither of us mothers paid a cent for childcare. Best of all, the two boys, who are now in 10th grade, are still best friends.

Homework

The older kids get, the more homework they’ll be required to do. This can take a lot of time and focus—and they’ll have more of both if they’re off screens! The amount of homework they get will vary based on the grade, school, and proclivity of teachers, but homework can easily take up 1-3 hours of a teen’s evening (less if they’re not distracted by a phone), which helps to fill that void in a highly productive way.

Chores

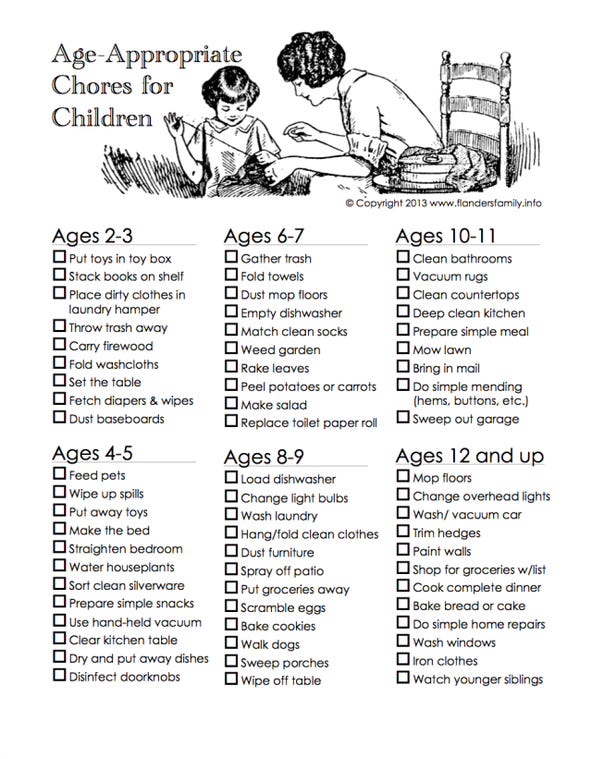

Putting kids to work around the house helps not only to fill the void left by a lack of screen-based entertainment, but it allows them to develop practical skills that they will need someday. Training for adulthood is cumulative; and the sooner you start and more consistent you are, the easier it will be for them to set out on their own after high school. For inspiration, check out the following list of age-appropriate chores, created by Montessori:

Music

I am a fan of formal music training for children. I realize that not everyone has access to resources that allow this, whether financial or geographic, but I grew up in a fairly poor family playing violin and piano (my parents put all their extra money toward music lessons), and I have done the same for my kids from a young age. They are expected to practice each day, which is an ongoing battle—as it is for anyone who commits to a musical instrument. No kid likes practicing, especially when it takes up an hour of their day!

There are a few reasons I stick it out. First, they might actually fall in love with music and become professional musicians, in which case I’ll be glad I exposed them to it. Second, it gives them something to feel proud of, which kids need. Finally, the act of daily practice teaches them discipline, which is a tough thing to teach in an increasingly urbanized and digitized world. We don’t live on a farm where I can send them out to milk cows, shovel manure, or chop wood early in the morning, but I can make them grind away at scales, studies, and repertoire before going to school every day.

I’ll never forget what my mother once said to me when I felt discouraged by one child’s slow progress:

The real point of music lessons is not to get good at an instrument. It’s about discipline. You’re teaching your kid to sit down and do something hard every single day, even if he doesn’t like it. Getting good is just a bonus. But you’re not wasting time by teaching him discipline that can be applied to everything else in life.

Sleep

A child who isn’t on screens can sleep far more than a child who is! When parents wonder what their kids will do in the evenings without a tablet to entertain them, I say, “Put them to bed earlier.” You may have heard the notorious line from Netflix’s CEO, saying the company’s main competitor is sleep, more so than other streaming platforms. It’s disturbingly accurate, though. Take the devices away, and suddenly bedtime becomes a whole lot more appealing for the entire household.

Nothing!

Last but far from least, you don’t have to do anything with that leftover time. You can let kids just be. Allow them to get comfortable with facing swaths of unscheduled, empty time. Let them be quiet. Boredom is a deeply rich creative state. It can feel uncomfortable in the moment, but a child must move through it in order to get to the other side. It’s a precondition for developing new skills, hobbies, and interests; and when we deprive children of boredom, we make it harder for them to become good at new and hard things.

Kids are marvellously adept at resolving their own boredom, as long as parents get out of the way and leave them to their imaginations. Subtract yourself, as I’ve written before, in order to give your child room to grow.

You Might Also Like:

CTV The Social – Toronto, ON

I had my first life TV appearance yesterday on CTV The Social in Toronto. It was a ton of fun! I’ve never worn so much makeup in my life (it was done in-house), and there were a lot of lights and cameras pointing in my face, but everyone was warm and welcoming, and it helped to have the live audience there to engage with my comments.

Globe and Mail Opinion – June 16, 2026

My once-monthly piece for Canada’s largest newspaper, the Globe and Mail, came out this past Monday. The title (which I did not write) is, “No, your teen shouldn’t rot in front of a screen this summer.” As usual, it sparked lots of comments, including some interesting observations about teens struggling to find summer jobs. As my oldest embarks on a job hunt this week, I’m curious to see what his experience is—and why that might be the case.

This is a great place to start. May I suggest board games too? They are a great way for teaching so many skills inherently! Bonus: older kids teach younger kids how to play!

"Resist the urge to view this as clutter. Part of encouraging analog play is accepting that there will be mess and visual chaos at times. If you rush to clean it up, you deprive your kid of the opportunity to get back into a project again, so try to let it be (within reason!)."

Thank you for making this point. This is SUCH a critical part of making the switch away from screens for parents. You have to be comfortable with mess. If kids are not on screens, they are being kids! Playing, creating, exploring, pretending, and all of that is messy. It's HARD and I am constantly telling myself it is okay to have a lived in house.